How to build and manage cross-functional teams for better outcomes – Part 1

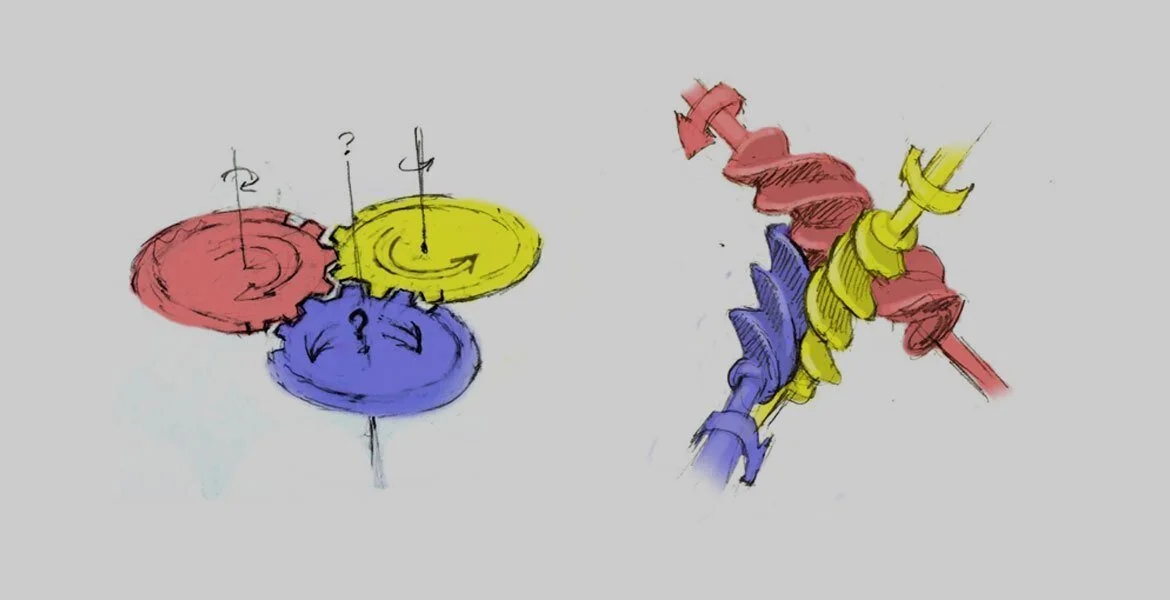

Top image by TeamFit’s David Botta, inspired by Three Gears Are Possible on Numberphile.

A guest post by Adi Kabazo

As a product professional, I’ve had the opportunity over the years to be a member of or leader of cross functional teams. These teams tackled a wide array of issues, typically in project or time-bound committee formats. The matrix organizational structure and cross departmental collaboration through the lifecycle of selling and supporting products and services make cross functional teams a natural occurrence in many modern organizations.

The project management methodologies and how stringently they are followed, the role of project sponsors and their degree of influence, the existence of a Project Management Office (PMO) and other factors shape the project management experience in an organization. The cross-functional teams I have been a member of typically followed a gated process, whether loosely defined or on the stricter side of the spectrum. Of course no two organizations are the same. So while your mileage may vary, this is written based on extensive experience in initiatives such as development and commercialization of new products, planning and execution of go-to-market (GTM) campaigns and the investigation into or implementation of process improvements in various areas of operations and customer service.

Please take this short survey on the skills that are driving success in professional services.

In this post and the one that will follow, I will give you my recommendations on how to get better outcomes from cross functional teams. These insights are from the perspective of a project sponsor and key contributor on such teams, not a project manager. In this post, I will cover team creation, including items such as the composition of teams, establishing the project mandate and more.

Building the cross-functional team

The formation of successful teams is one of the most critical and elusive challenges that modern organizations face. This is despite many advances in areas of management such as project, human resources and business in general.

This post was inspired from conversations I have had with the folks at TeamFit, a company that has dedicated itself to tackling the challenge of creating and managing teams for better project outcomes.

Seek a blend of skills, experience and perspectives

By assembling cross functional teams, organizations are trying to assign complex tasks to a collection of professionals with the right blend of skills and domain expertise. The skills and experience directly related to the tasks is not the end of the story. Perspectives matter too. Ensuring that the team brings a balanced range of perspectives from various functions is critical to initiatives that span the organization. Diversity of ages, cultures and even cognitive and emotional styles can can bring insights into potential challenges and opportunities. This is particularly true for initiatives with customer experience implications (marketing, sales, service etc.).

Get the right team size

Find the right team size can be tricky. A project supported by a small team may take longer to produce results. This is true even though the team is easier to manage and if it has all the necessary skills, experience and perspectives. A larger team provides more flexibility to allocate responsibilities and assign tasks, but presents the risks of inefficient communication, coordination challenges and declining engagement. Additional tips on ways to enable efficient collaboration and improve ongoing management of cross functional teams will be covered in the second post of the series.

Understand and communicate expected levels of commitment

Even before the team is formed and as a project manager is being allocated (or assigned) to the initiative, the project sponsor should work with the project “champions” (key representatives from the business unit leading the initiative) and start identifying the skills, areas of expertise and the resources required. Some people will need to be allocated on a full time basis and make part of the project’s “core team”. Others will be involved on a part time basis due to other project or day-to-day responsibilities but will be expected to contribute to the initiative at varying levels. Some resources will only need to contribute at later stages of the project but timely involvement even in a monitoring capacity (with occasional input) is critical to the effort. Nothing can throw a project off schedule more than people missing timelines for input and feedback.

Clarify responsibilities

Whether team members are allocated to the project full time or part time, are employees, contractors or even supplier representatives, it is critical to establish clarity on everyone’s responsibilities. This is the necessary foundation for accountability. The responsibilities may evolve throughout the duration of the project strengthening the case for clearly capturing and communicated the for everyone to see. One tool that facilitates such clarity, despite the time and effort to produce it, is the RASCI model. Paraphrasing the old quote, it’s about the journey, not the destination – the process of negotiating responsibilities with the various stakeholders is a great way to uncover potential gaps and challenges. Time spent on this at the beginning will save time later on.

Strive for continuity

One of the more challenging situations I’ve encountered over the years in projects that spanned extended periods of time have been when team members were “pulled” from the project and reassigned by their functional group to other initiatives (whether these were more strategic or distressed). Such departures result in lost knowledge and are detrimental to some intangible project achievements such as team alignment, trust and camaraderie. Such occurrences may be more prevalent in organizations where the skills or expertise of certain team members, let’s refer to them as “experts”, are scarce and thus highly desirable. One proactive way to address this issue is to apply some redundancy for the skill by including additional team members to “shadow” or support the expert. This approach can provide team members with a growth and learning opportunity to further their career in the organization but it also adds cost and may diminish the accountability sought. Another recommended course of action is to set the expectation with the functional group supplying the expert that it is its responsibility to address these situations. This should incorporate not only backfilling the project role with another team member but also by ensuring a smooth and effective transition to the new team member.

Establish a shared charter and objectives

Unless it’s a secret initiative (or project), a definition of the situation, the project’s key objectives and its initial timeline would already be established at some level even before funding is secured and resourcing beyond the first core team members takes place. As compelling the current definitions or commitments are, these should still have flexibility to incorporate team member input while the cross-functional team is being formalized towards the project kickoff. Understanding the different motivations of project contributors, incorporating ideas contributed by the team and aligning everyone on the project charter and common objectives are key to both establishing trust and setting an important foundation for engagement.

In the next post in this series we will discuss some of the challenges and opportunities in the ongoing management of projects. We will also review the importance of executive visibility and consider areas to improve it such that overall project health, risks and progress are proactively managed.

About the author

Adi Kabazo is the owner of Objective Innovation (http://www.objectiveinnovation.com), a firm dedicated to guiding technology businesses with their product and channel strategies as well as implementing customer focused product and marketing practices to provide greater value to their customers and users, facilitate new business models and promote scalable sales and delivery operations.

For much of his 20+ year career Mr. Kabazo has held key product and marketing strategy leadership roles for innovative software and hardware technology companies. Mr. Kabazo strengths in business planning, commercialization and operational delivery were key to growth, customer success and in several cases acquisitions that resulted in significant return for shareholders.

Adi holds a Bachelor’s degree in Industrial Engineering from Tel-Aviv University in Israel and received his Master’s degree in Business Administration from the Sauder School of Business at UBC. He was also the co-founder of Vancouver ProductCamp and is past Chair for the British Columbia Technology Industry Association (BCTIA) Product Management Group.