High stakes decisions under stress – your field of vision limits the choices you can see

In June our team successfully completed a major piece of work. It was high stakes and high pressure, with a lot of late nights and some pretty intense conflicts. But we made it through and we decided to celebrate by taking a day off and going on a canoe trip (what can I say, we are based in Canada).

We headed up to Widgeon Slough, a large wetland where the Pitt River flows out of Pitt Lake. It is an area four generations of my family know, one of the places I like to spend time, so I was the leader for the trip. There were about twelve of us in four canoes.

Most people go up the left (western) branch but I prefer the more isolated right (eastern) branch with its miraculously clear water. After lunch on a sandbank, three of the canoes went up further to see if we could get around a fallen log and go higher into the head waters. (The other canoe headed back to encounter a bear swimming across the entry of the slough, which gave our QA lead, who comes from Northern India, a bit of a pause.)

At the log we got off and dragged the canoes onto the water on the other side. The log was slippery, very slippery. Covered with moss and algae. A young media expert in the third canoe slipped and fell into the very cold water between the canoe and the log.

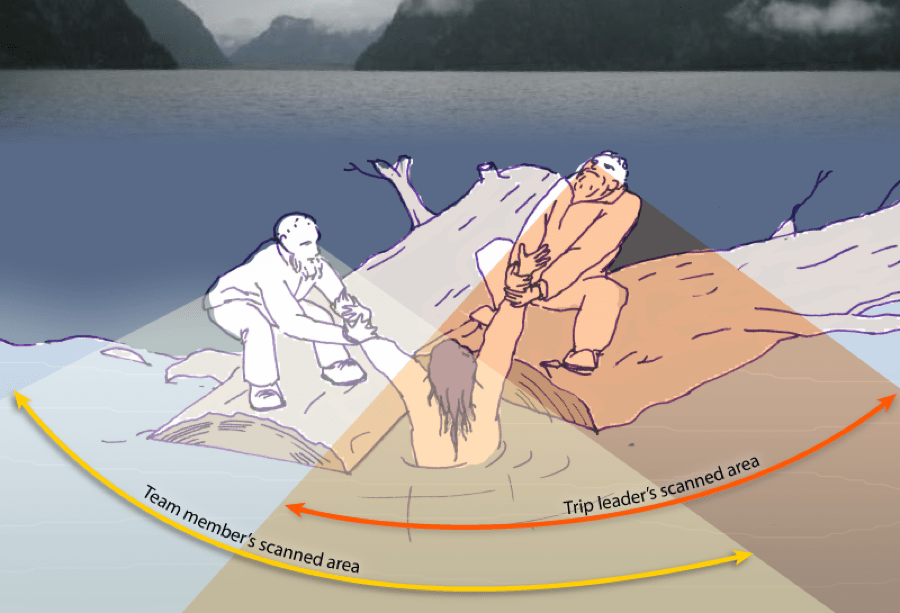

She was one of the younger people on the team and did not have a lot of experience in the wilderness. I was standing on the east-side of the log, one of our engineers was on the west. Both of us had poor footing. Above us, upstream, was a strong current pushing up then under the log. Danger. Falling in above the log was a high risk.

We each grabbed an arm and tried to pull her up out of the water, but we were both afraid of losing our own footing and falling backwards. My partner in the rescue shouted that we could move to the west on the log, to shallower water. I responded that we should go east to a place with a lower ledge.

I was senior, more experienced, and I could not see past my partner to the escape route he was advocating. For a moment, we each pulled opposite directions! Then I prevailed and we slide East along the log to the ledge and got our colleague to safety.

When I analyzed the situation later I realized we (I) had chosen the worst of the three options available.

We could have had our colleague grab the canoe and then taken her maybe 10 meters downstream to a sandbank where she could have rested and then gotten back in the boat. This was the safest choice and what we should have done.

We could have eased her over to the shallower water on the west side of the creek, where she could have stood up on her own.

We pulled her over to the ledge on the west side where we were able to get her up on the log. This was the worst option as it (i) made us move on the slippery log and then (ii) required her to walk along the log to safety.

Why did I make the wrong decision?

Immediate action was needed to stabilize the situation. That action was to get hold of the person in the water. We did that. Good. But then instead of pausing to reassess we just continued right along and tried to get her up on the log. We should have paused, had a brief conversation to lay our options and then decided.

I acted only on the information available to me and did not use the wider frame of reference that would have been available if I had asked my partner what he was seeing. I could not see the escape route to the west so remained fixated on my first decision.

My partner had a better idea on what to do, but as I was senior, and was feeling responsible, I did not really listen to him. I was fixated on executing my own solution as quickly as possible and did not listen to a better idea from a person in a position to see things I could not see.

What could I have done differently?

After stabilizing the situation, reassess.

Talk to the people around me to get a wider view than any one perspective could provide.

Be prepared to let go of my own solution if a better one presented itself.

Look (quickly) for a solution outside the box. In this case it would have been going downstream and not trying to get the person in the water on the log.

A final point, after we were all safe we still had the slippery log to deal with. My partner had a simple solution. He took sand from the bank and we coated the top of the log. This gave us a good footing to handle the canoes from. I like the way engineers think!

Even with all the excitement we all enjoyed the trip and it has become part of the company culture. Next, we plan to go kayaking together, probably from Deep Cove but possibly over in Montague Harbour on Galliano Island.